We’re pretty tied up right now with the work needed to get

Stupefying Stories #24 finished and ready for release next week, and

Trunk Story Week had a mid-air collision with Chemo Week and thus our planned posting schedule got a bit scrambled. Ergo here, for your entertainment, is yet another old story of mine that spent a few years in the trunk before being published. Afterward I’ll have a bit to say about what made

this one a trunk story in the first place, and what I had to do in order finally to be able to

sell it to a pro magazine.

Enjoy!

~brb

___________________________

A CONTRACT FOR MEYEROWITZ

by Bruce Bethke

First publication: Science Fiction Review, August 1990

It took ten minutes of standing in the shadows,

hand on the gun in his pocket, before Ed Meyerowitz felt ready to cross

the street and go in. Even for a Monday night, the old warehouse, loft,

and boutique district was deserted. A strange mixture of sweet

excitement and sickly fear churned in his gut, as he kept watch on the

café across the street and listened to the soft noises seeping through

the cool October air. In his mind, Karl Larsen's voice reproached him

one last time.

"Eddie," he remembered Larsen saying, "we're on to something big

here. They won't stop halfway once they decide to silence us." He'd

laughed at Karl then, for sounding like an extra in a Spillane story,

and accepted the gun only to humor him. Now Meyerowitz found himself

caressing the Beretta's cold, hard grip and desperately trying to work

up a grim and determined mood.

The trouble was, he kept reaching the same conclusion: if he were anywhere near

sane, he'd throw the gun in the river, go home, and forget that

anything had ever happened. As soon as he'd reach that decision, though,

he'd look at the café again, and once more get sucked in by curiosity —

curiosity flavored with a seductive hint of importance. It'd been so

long since he'd done anything that felt important.

And so

he'd flip-flop, and decide to work on his nerve a little longer. The one

thing he knew for certain wasn't helping any. No one had seen Larsen in

over a month.

Like the unbidden memory of a bitter taste, he remembered the day Karl first proposed their little scam...

¤Ed

Meyerowitz was ad manager for a weekly shopper. Karl Larsen ran a

one-man advertising agency. Business threw them together, and it'd only

taken them a few beers after work one day to learn they shared the same

real profession. Both were unpublished Science Fiction writers.

Larsen

was 31, Meyerowitz was 28. Larsen was divorced, and Meyerowitz had

never married. They'd taken to getting together once a week to swill

coffee and discuss life, fiction, and the state of the universe. A year

before, Meyerowitz had been sitting in Larsen's kitchen, trying to

rebuild his ego after yet another rejection of The Novel and doing a lot

of grousing about The Hidebound Publishing Establishment.

"Eddie," Larsen had interrupted, "this fiction business is definitely not

where it's at. We do our best to be creative and what do we get?

Condescending smiles from Post Office clerks!" Larsen paused, to run a

hand through his thinning hair. "No, if we were smart, what we'd

be doing is writing supermarket nonfiction. I mean, we could write jock

biographies, or self-help books. We could write about UFOs, or Bigfoot,

or —" Larsen suddenly froze, stricken with inspiration. "Eddie, I've got

it! We're going to write the ultimate conspiracy book! One that links war, crime, and every assassination since Lincoln!"

Meyerowitz paused in the middle of pouring more coffee. "Karl," he asked gently, "are you having another Idea Attack?"

"No." Karl shook his head, his eyes blazing with manic intensity. "This one will work! Ed, I've just realized that the world today is such an ugly place because someone is manipulating mankind to be violent! And I further believe that we can do a book on it, give people someone to blame, and turn a lot of bucks!"

Meyerowitz sighed, and finished filling his cup. "Is this another corporate conspiracy rap? Last week you said cancer—"

"No, not multinationals," Larsen cackled. "Bigger."

"Okay, bigger. Fascists? Communists? Trilateralists?" Meyerowitz narrowed his eyes. "Don't you dare say Jews."

"No,

man," Karl giggled. "We're talking cosmic. We're talking outer space.

We're talking Bermuda Triangle, Ancient Astronauts, the Fall of

Atlantis, and Dead Kennedies, all rolled into one. We're talking BIG!"

"You don't mean...?" Meyerowitz started snickering.

"Yes, I do mean. Aliens! They're too cowardly to invade, so they keep stirring us up in hopes we'll kill each other off!"

"I can see the front page of the Enquirer now," Meyerowitz said. "NEW SECRET EVIDENCE: HITLER WAS A SPACE ALIEN!"

"Good

thinking." Larsen pulled a notepad out of the heap on his kitchen

table. "We'll do some articles for the tabloids first, to build market

presence." He took off his glasses and chewed an earpiece. "If we handle

this right, it'll be good for three books, minimum. Maybe even a

made-for-TV movie."

"Oh, come on," Meyerowitz said. "Do you really think—?"

"Without

a doubt. Velikovsky. Cayce. Van Daniken. There's no limit to the

shamanism disguised as science that stupid people will lap up. We'll do

some superficial research, ignore inconvenient facts, misinterpret the

findings, bash out a few books—"

"And publish them under your name," Meyerowitz declared.

"My name? You still want a reputation after this?"

"No. But when sales start to lag, we write a book under my name that refutes the whole thing! We could keep this going for years!"

"I like it!" Larsen crowed.

¤They'd

started with a fast-paced routine. During the week they collected odd

statistics, bizarre articles, and every bad UFO photo they could find.

Then, on Sundays, they'd meet at Larsen's to drink beer, clip pages, and

randomly reshuffle paragraphs. This went on for three very promising

months.

On the last Sunday in January, though, something went terribly wrong.

"Here's one," Meyerowitz announced as he flipped open the tabloid. "ALIEN REPAIRMAN TURNED MY TV INTO A TIME MACHINE! Now I only get programs from the 1950s!

says distraught housewife." Meyerowitz looked at Larsen, smirk cocked

and ready. "Sounds to me like her tuner is stuck on WTBS."

Larsen just sat and stared glumly at the box of clippings.

Meyerowitz shrugged and continued. "Okay, try this one. RUSSIAN ASTRONOMERS FIND INTACT B-17 ON MOON! It's covered with green slime, which proves it was captured in the Bermuda Triangle." Meyerowitz nodded. "How about it, Karl? How big a telescope do you need to resolve an airplane at a quarter-million miles?"

Larsen continued staring silently at the box.

Meyerowitz threw the tabloid down. "That tears it. Karl, you haven't said three words all afternoon. What's going on?"

Larsen

sat a moment longer, then slowly began to speak. "Eddie?" he said

softly. "I'm beginning to get some very chilly feeling about all this."

Meyerowitz started to say something, but Larsen waved a hand to cut him

off. "I haven't had to do as much fudging as I expected. I haven't had

to invent a single fact, or fabricate a single misquote out of context.

The ideas are falling into place without my hardly trying."

Larsen turned to Meyerowitz, his eyes wide and pleading. "Eddie? I'm starting to believe we accidentally stumbled onto the truth."

Meyerowitz

took a sip of beer, carefully set the bottle down, took in a deep

breath, slowly let it out, and then said, calmly and quietly, "Now, let

me get this straight."

The argument lasted all through February.

¤A

bus rumbled away from the traffic light on Third Avenue. Meyerowitz

took the Beretta out, pulled the slide back just far enough to reassure

himself that there was a round in the chamber, eased it shut again, and

then started across the street. In the end, he realized, it was

curiosity that had gotten the better of him. Trying to shake the image

of a dead cat out of his mind, he slipped the gun back into his pocket

and entered the café.

A lone, bearded waiter leaned against a doorframe at the back of the

café, smoking a black Sobranie. A bell chimed softly as Meyerowitz let

the door close behind him. The waiter sighed heavily, balanced his lit

cigarette on a convenient ledge, grabbed a couple of menus, then gave

Meyerowitz's tweed jacket an appraising look and decided to go back to

finishing his cigarette.

Except for the waiter, the place seemed

deserted. Meyerowitz felt queasy with doubt — could he have botched the

instructions? No, no chance of that. The voice on the phone had been

quite explicit about the place and time. Staying close to the wall, he

edged cautiously into the café.

"Good evening, Mr. Meyerowitz,"

someone said behind him. Eddie spun around, jabbing his hand into his

jacket pocket, groping for the gun — and then he left it there.

A

pudgy, fiftyish man with a weak smile and watery blue eyes sat in the

booth to the left of the entrance. His skin was a healthy, baby-pig

pink; his hair a mousy shade of brown, gray at the temples. He was so

non-descript that Meyerowitz had simply walked right past without

noticing him. In fact, the only odd thing about the man was that he wore

conservative gray pinstripes in a café that catered to the fashionably

trendy.

A perplexed look crossed the man's face. "Er, you are

Mr. Edward Meyerowitz, aren't you?" Darting a nervous glance around the

room, Meyerowitz nodded. "Splendid. I am Gordon Smith." The man rose

and offered a handshake.

Meyerowitz ignored Smith's hand and dropped into the opposite seat. After a moment's awkward hesitation, Smith sat down.

The

waiter wandered by, but Meyerowitz waved him away. "Not hungry?" Smith

asked. He picked up a fork and prodded the food on his plate. "A pity.

The quiche d'jour is exquisite."

Meyerowitz studied Smith

minutely, but could not decide if he should feel angry, frightened, or

silly. After a brief and uneasy silence, Smith's smile faded. "Well, I

see you aren't disposed to make this pleasant, so I'll come right to the

point.

"Mr. Meyerowitz, it has come to our attention that you

have in your possession all the research, all the rough drafts, and

every extant copy of a certain book written last winter by yourself and a

Mr. Karl Larsen. I'd be very interested in purchasing that material."

Meyerowitz stared at Smith a moment longer, and settled on angry.

"Really, now?" He was startled by the tremor in his own voice. "Then I

suppose you also know that our original publisher reneged on our

contract."

"I'd heard something to that effect, yes."

"We

went from having four major houses bidding on it to not being able to

find an open transom to pitch it through. Even our agent got an unlisted

phone number and didn't tell us." Meyerowitz slouched, to point the

pistol at Smith under the table. "I'd really like to know why you want such an obviously unsellable dog."

Smith

smiled weakly. "We've been most impressed with Mr. Larsen's

determination to see the book published, despite the remarkable run of

bad luck that's followed it."

"Bad luck? We couldn't even find a subsidy

publisher. I was ready to call it a stiff and give up, but Karl

insisted it just proved we were right and got a second mortgage and

published it himself. Then the printer's strikes started."

Smith laughed mildly. "Fate takes strange turns, no?"

"Especially when it has help."

Their

stares interlocked. The impasse was broken only by the waiter's next

approach; this time Smith was the one who waved him away. "All the

same," Smith said, suddenly turning cold and brusque, "we're not here to

talk about the past. We're here to discuss a mutually profitable

business proposition."

"Like the one Karl got?" Meyerowitz hissed.

He leaned in close, and tightened his grip on the gun. "I have the

books because the bindery couldn't deliver them to Karl. I've been

asking around; no one has seen him in over a month. So drop the façade.

Who are you, really?"

Smith looked perplexed. "Why, I didn't think

I'd made a secret of that. My name is Gordon Smith. I represent a major

New York publisher whose name discretion will not allow — "

"You

don't understand. I'm pointing a gun at what I believe to be your balls.

Now will you..." Meyerowitz paused, taken aback by the change in

Smith's expression.

"Oh, dear," Smith gasped. "Please d- d- don't

—" His jaw seized up, and he began quivering like a mannequin made of

Jell-O. Meyerowitz stared in horrified fascination as a string of

spittle ran out of Smith's open mouth and oozed down the front of his

Brooks Brothers suit.

"Larsen got an offer he couldn't refuse,"

another voice said. Meyerowitz spun in his seat to find the waiter

standing beside him. "Put the gun away, please. You're giving poor Smith

a heart attack." Meyerowitz froze, uncertain. Smith did indeed seem to

be a gibbering wreck — but was it a ploy? Would he spring the moment

Meyerowitz dropped his guard? Or did the waiter have him covered with

something more lethal than that damp towel? Which one? Meyerowitz's inner voice screamed. Involuntarily, he clicked the safety off.

"For

chrissakes, Eddie," the waiter sighed, "don't be a putz." Meyerowitz's

trigger finger froze; something in the voice seemed very familiar. The

waiter raised his hands to his face and began peeling off ragged pieces

of artificial skin.

"My God!" Meyerowitz gasped. "The unmasking!" The waiter dug fingers into his flesh and tore off his face to reveal—

"Karl?" Meyerowitz's jaw went slack.

"Yeah, Karl."

Larsen pulled up a chair and sat down. "I wasn't supposed to let you

know I was back. Muffin, here," he jerked a thumb at Smith, "wanted to

prove he could handle you all by himself."

"But...?"

"It's their version of machismo. Every one of them secretly believes he can out-talk a used car salesman."

Meyerowitz swallowed hard. "Karl, are you...?"

Larsen

picked at a bit of latex make-up. "Working for them? You bet! I figured

it out about a month ago. Didn't you?" Something in Meyerowitz's face

gave away the answer. Larsen snickered. "And you call yourself a science

fiction writer!"

Meyerowitz's expression resolved into a fierce

scowl. Bringing the pistol out from under the table, he pointed it at

Smith and hissed, "Karl, he's the enemy!"

Larsen shook his head. "No, Eddie, he's just — Eddie, will you please put the safety back on that effing thing?" Slowly, Meyerowitz complied. Smith seemed to start breathing again.

"Thank

you," Larsen said. He cast a mildly concerned glance at Smith, then

went on. "Once I read the book in galleys, I spotted the hole in our

thinking. We figured the aliens were too cowardly to invade." He looked

at Smith again, and gave a disgusted snort. "We got the coward part

right, anyway.

"But Eddie, there are at least a dozen cheap and

easy ways to wipe out a species from low orbit, and some of them don't

even do serious damage to the ecosphere! So I got to thinking, why else

would they be breeding us to be violent?" He studied Meyerowitz a

moment, then softly suggested the answer. "Why do we have military

schools, Eddie?"

Larsen didn't wait for a reply. "They're an

ancient race, Eddie. Wise, kind, peaceful — too gentle, in fact, for

their own good. That's why they need us. New recruits, to defend them

from the real nasties." Larsen shrugged, then helped himself to

Smith's Perrier. "Once I figured that part out, the rest was easy. They

were looking for a new North American PR guy. Seems they hired the guy

who torpedoed our book away from a union in New Jersey, and he had a

difference of opinion with Smith's predecessor. Broke both his legs."

Larsen reached over and gave Smith a friendly little fake punch on the

arm. "Lucky break for you, eh, Gordo?"

"The book," Smith gasped. "Get the book."

Larsen

shrugged, and turned to Meyerowitz. "That's it in a nutshell. We're the

Marines who man their starships. To them, your average human being

seems like a regular Conan."

"The book," Smith insisted.

"I'm getting around to it," Larsen snapped at Smith.

Meyerowitz

considered Larsen with narrowed eyes. All sorts of old doubts were

suddenly resurfacing. He'd always found Larsen just a tad too glib, too

eager to sell out. Now one big question was forming in his mind: Do I dare trust Larsen?

"Why are they so afraid of the book?" he asked sharply.

"They're

the ultimate passive-aggressive basket cases. Confrontation absolutely

terrifies them. If they're exposed, they'll pull out."

"So?"

Larsen

studied Meyerowitz's face a moment. "That's wouldn't be good, Eddie.

Sure, they've caused a few wars. But they've also given us most of our

modern medicine, and in five years they're going to give us real

interstellar spacecraft. For chrissakes, Eddie, Von Braun was one of them!"

Meyerowitz's thoughts took a very cold turn. "Better tools to make us better soldiers," he said softly.

"Yeah,

well —" Karl shrugged. "We can argue the ethics of it another time,

okay? The point is, they want your share of the book. You want to sell?"

Meyerowitz looked to Smith, whose face was still deathly pale, then back to Larsen. "How much?"

"Ten thousand," Larsen said flatly.

Meyerowitz pretended to think it over, while his anger burned hotter. "I don't know. What kind of royalties are we talking?"

"Royalties?" Smith whispered.

Meyerowitz smiled wickedly. "Of course. I'll want a percentage for every copy you sell."

"There must be no copies sold!" Smith gasped.

Meyerowitz feigned an offhand shrug. "Oh. In that case, ten grand sounds pretty cheap for burying the truth."

"Eddie—" Larsen began.

"Fifty thousand!" Smith blurted out.

Larsen turned on Smith. "You keep out of this!"

Meyerowitz dropped the façade and let his anger flow. "A crummy fifty thou to play Judas to an entire planet?"

"A million!" Smith pleaded.

"Shut up!" Larsen snapped.

Meyerowitz

stood. "I'm leaving before I decide to use this gun." Then he paused,

and glared at Smith with unabashed hatred. "And yes, I'm releasing the

book."

Smith's face went utterly white. "Five — ten — any — "

"I told you it wouldn't work!" Larsen hissed. "Go to Plan B!"

Meyerowitz whipped out the Beretta and spun around. "What's Plan B?"

Smith fainted and fell face-first into his quiche.

"Plan

B," Larsen said gently, "is this." Slowly, carefully, and with a great

show of non-threatening behavior, he gently lifted Smith up and

retrieved a fat envelope from his inner breast pocket. Then he let Smith

flop back into the quiche.

"What's that?" Meyerowitz asked suspiciously. "You think I'll find cash in hand more tempting?"

"Nothing

so crude," Larsen said. He opened the envelope and pulled out a sheaf

of papers. "This is an honest-to-God book contract. Ten grand advance,

plus royalties. You should have believed Smith. He really does work for a

major publisher."

Meyerowitz scowled at Larsen. "And this is the

part where you offer to buy my soul, right? I can have it all — fame,

fortune, and a guest shot on Donahue — if I just sign that contract. Oh, but you reserve the right to 'edit' the conspiracy book?"

Larsen looked up, all injured innocence. "What conspiracy book? This is for Swords of the Capellan Moon."

Meyerowitz froze.

"That's

right, Eddie," Larsen said softly. "Your novel. In the past year you've

collected sixty rejection slips and not sold so much as a Campus Comedy. I can change that, Eddie."

Meyerowitz felt his iron resolve beginning to waver.

"In

fact," Larsen — mindful of the gun Meyerowitz still held — carefully

reached across the table and opened Smith's briefcase, "I just happen to

have another contract here, for a series I'm packaging. Nine books in

all, about a handsome young hero from Earth who's sort of a galactic

Lone Ranger for a wise old race called the Mentors." Larsen extracted a

second contract from the briefcase and carefully laid it on the table.

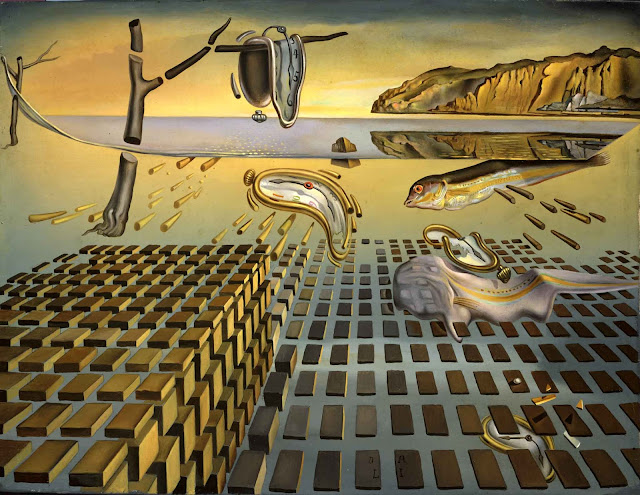

"Granted,

it's strictly space opera," he went on. "Lots of rockets and ray-guns,

action and adventure, a little soft-core sex. Our hero always fights on

the side of justice, and he always fights nobly — but hey, I've got this

great Larry Blamire cover art here that gets the whole concept."

Karl slipped a large, glossy, color print out of a manilla envelope and

held it up so that Meyerowitz could see it.

It was an action

scene: a hero, center-stage, surrounded by hordes of ravening alien

monsters. In one hand he held a massive, blazing handgun; with the other

he sheltered a cowering, half-naked blonde beauty. The bulging thews on

the hero's bare arms were straight out of a Marvel comic book.

But his face was unmistakably Eddie Meyerowitz.

"I... I can't bury the conspiracy book," Meyerowitz gasped.

"What conspiracy book?" Larsen asked innocently. Putting the artwork down, he uncapped a pen and set it next to the contract.

Meyerowitz

looked at the cover art, and then at the Beretta in his hand. The

little automatic seemed like such a tiny and stupid thing. The man on

the cover: now there was a Hero. There was a man who could save worlds with his bare hands.

"Nine books?" Meyerowitz whispered.

"Guaranteed print run of a hundred thousand copies each. And the first one can be in the stores by Christmas."

Meyerowitz

was right-handed, so he had to put the Beretta back into his pocket

before he could pick up the pen. "Fiction reads better, anyway," he

said.

____________

A Contract for Meyerowitz: A Tale from the Trunk

In hindsight, I'm amazed I ever managed to sell this one. There are

so many things wrong with it that it just should not have sold, period.

The fact that it did merely proves that for every rule, there is an

exception.

This should not be misinterpreted as proof that the

rule is invalid! It simply means that from time to time, even

professional editors experience moments of weakness.

I wrote the

original story in 1983. Between December of 1983 and June of 1985, I

shopped it around to... Well, that's hard to say. I sent it out twelve

times, total, but two of those markets turned out to be out of business

by the time my manuscript got there. Another of the "markets" actually turned out to be a "contest" being run by a so-called literary agent, apparently

as a racket to find writers willing and able to pay cash for the

services of a "professional story doctor." (Simple advice which you

should never forget: any so-called editor, agent, or publisher who tells

you your story isn't marketable as-is, but would be salable with a

little help from a professional story doctor {and they just happen to

know one who would be perfect for you}, is not in fact an actual

editor, agent, or publisher, but rather a parasitic organism feeding on

the hopes and dreams of writers. Such creatures, when encountered, should be treated with the

same regard you would accord any other leech, tick, tapeworm, or similar

bloodsucking parasite.)

In total, then, it went out to nine

viable markets, and came back with six plain form rejections and three

form rejections that included a handwritten note to the effect that the

story was too much of an inside joke. Ergo, in July of 1985 I retired

it.

Three years later, when I'd made it up to selling stories

fairly consistently, I pulled it out one day, decided it was

salvageable, and gave it another rewrite. The main thing I did was

tighten it up by about 500 words. I lost one bit of detail I should have

kept: in the original manuscript, I identified the gun very

specifically as being a Beretta Jetfire in .25 ACP. In hindsight, this

was a key detail, because in the early 1980s Beretta was mainly known in

the U.S. as a maker of tiny and under-powered popguns, more useful as

threats than as actual weapons. (As Jeff Cooper once said of the .25

Beretta, "If you shoot someone with it, and they find out about it, they are apt to become highly emotional.")

In

1985, of course, Beretta landed the contract to replace the venerable

.45 caliber Colt 1911A1 with a high-capacity 9mm, and as a result they

are now known as the maker of large, clunky, and awkward under-powered

popguns. But that's a topic for another time.

Another thing that

vanished in the rewrite was — well, let's just say that in the original

manuscript Smith was a whole lot more "metrosexual" than in this

version. (Not that that word had been invented yet.) But I was

beginning to realize that editors were becoming very nervous about — er,

"flamboyant" characters, so I toned him way down.

[Correction: Allow me to speak plainly. One does not work in theater and music for as long as I did if one has a problem with gay people. Smith as originally written was not an offensive gay stereotype, as one critique group reader called him, but in fact was patterned very closely after a friend and theater director I’d worked with several times. Nonetheless, I learned my lesson: never write anything that might upset the LGBTQ crowd—not that that term had been invented yet, either.]

The third

and most important thing that vanished in the rewrite was a

two-paragraph diatribe Karl threw in at the end, comparing Frank

Edwards' Flying Saucers: Serious Business to Frank Herbert's Dune

and expanding on the thesis of the nine-book series that Meyerowitz is

being offered. That passage was pure dead weight and the story is

better for its absence.

Once I had the rewrite finished, I started

shopping it around again, and in short order collected one "Too much

like a Ron Goulart story I just bought," one "Too much like a Phil

Jennings story I just bought" (GRRRR!), two "This is just not funny and

not serious enough for [insert magazine name]," and an acceptance from,

of all places, Science Fiction Review, which published it a year

later, in the August 1990 issue.

So, looking back on this one from

thirty years later, what are the things I see as being wrong with it?

1. Narrative flow. It starts with a really nice noir

opening, and then immediately jumps into a long and winding flashback

that ends up consuming the first third of the story. "The Long

Flashback" is one of those things that was done to death back in the

1940s and has been held in low regard ever since. According to the

experts, this is the second most-clichéd way to start a story. (The

most-clichéd way, I've been told, is with a character regaining

consciousness and trying to remember where he is and how he got there.)

2.

Unnatural language. Karl and Eddie are forever addressing each other by

their first names. When you're having a conversation with a close

friend, and there's only the two of you in the room, do you feel

it necessary to use your friend's name in every other sentence? If I

were writing this story now, I would be more economical with dialog, use

far fewer italics and semi-colons, and wage a war of extermination

against the said-bookisms. (Example of a said-bookism: "It's sunny

out," he said brightly. Unless there's some possibility for confusion

about who's talking, it's usually not necesary to use the *.said

construction, and the adverb modifying "said" pushes it from merely

unnecessary to downright ugly.)

3. The Plot! This is the

big, insoluable one. What's this story about? It's another "unsuccessful

sci-fi writer invokes otherworldly aid to become a successful sci-fi

writer" story! This is a field that was worked to exhaustion back in the

1940s and turned into a dust-bowl in the 1950s, and there is not enough

manure in the world to make it fertile and green again.

At least,

that's what I've been told. Given that I was not around to read the

science fiction of the 1940s when it was new, I think I can be forgiven for not knowing

what the old guys had seen and gotten tired of before I was born.

4. And this is a biggie: The entire plot turns on the naïve assumption that

releasing a book means people will pay attention to it!

I imagine the

nutjob who writes all those Reptiloid Conspiracy books feels the same

way. For one of the shadowy masters who have been running our planet ever

since the dark ages, Smith sure ain't much. If I were to write this

story now, I could have Smith utterly crush Meyerowitz's heart and soul

with just a few well-chosen words about how the publishing business

really works. Or maybe, have him accept the conspiracy book, live up to

the terms of the contract, give the book nationwide saturation coverage

-- and still utterly destroy Meyerowitz's message and reputation, simply

by giving the book the wrong cover art treatment and promoting it with

quotes from people on the GRAI list.

You know, people "Generally Recognized As Idiots." You know who I mean.

5. Finally, the whole story really is too much of an inside

joke, and as such it violates the cardinal rule of insider jokedom. The

whole point of being in a group is to be able to look down on the people who are not in the

group. Certainly, it’s not to laugh at yourself.

When you're working in a genre, you have to remember that the people

who already write, publish, and read in that genre tend to be defensive

and have remarkably thin skins. If you write something that, however

obliquely, makes fun of the conceits of their beloved genre, you're toast.

It took a mystery writer, Sharyn McCrumb, to write Bimbos of the Death Sun. It took a playright, Neil Simon, to write The Cheap Detective. I'm told true-blue Trekkies hate "Galaxy Quest," because they feel it makes them look like idiots.

If you work inside a genre, never make fun of the genre. If you work

outside of the genre, then by all means, level the guns, load with

flaming shot, and fire away. But don't expect to publish it inside the

genre you're taking pot-shots at. In the ultimate hindsight, I should

have amped up the noir and suspense aspects and tried to publish this

one as a mystery.

Kind regards,

Bruce Bethke

___________________

Are you a published author with a Tale From The Trunk you’d like to share? If so, we’re looking

for writers who are both willing to let us reprint their previously publishing stories and brave enough to dissect

their own work for the educational benefit of the audience. Does this sound like you? Send queries only to stupefyingstories@gmail.com, subject line “Tales From The Trunk.”